Breve recordatorio fundamental de la geometría del Aikido.

O Sensei used these three principles to help his students better understand what they were learning. The Circle (marui), the Square (shikaku), and Triangle (sankaku) were used to illustrate the different concepts of movement and technique.

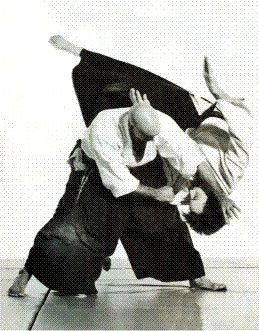

Triangle: O Sensei used the triangle to illustrate the idea of water flowing. He said that water always took the path of least resistance, and this is what Aikidoka should be doing as well. An example of a triangle movement would be the irimi, or entering techniques. As a sword is brought down to strike, the Aikidoka steps in and to the side in order to position him/herself for the defense. If we look at a triangle as having two angles at the bottom and one at point, we can imagine the two lower angles representing a very firm, stable base, and the lead point being the Atemi. The triangle can be compared to the irimi (entering) techniques because it gives the impression of direct movement, without a turn or a Tai-sabaki, just a quick forward technique. Sometimes the direct responses to an attack are very effective, and are excellent for unbalancing your partner.

"The body should be triangular, the mind circular.The triangle represents the generation of energy and is the most stable physical posture. The circle symbolizes serenity and perfection, the source of unlimited techniques. The square stands for solidity, the basis of applied control."

– O Sensei

Circle: Depending on your position and your opponent's balance, any technique can be executed from both the inside and outside of your partner's body. The circle comes from the japanese word Ju, meaning soft or gentle. The concept of Ju is the principle of pulling when pushed and pushing when pulled. We commonly hear the phrase "fight fire with fire", but I always thought that this was the opposite of the philosophy of Aikido. I think a more suitable phrase would be to fight fire with water. As circles we should never hit our opponent, no direct movements can be circles. The idea of the circle is to be like a ball, rolling with the attacks, usually by executing a Tai-sabaki to end up beside the attack. Being beside it effectively paralyzes the attack, because it is very hard to hit someone who is beside you and that close. When fighting directly, face to face, your opponent will have the opportunity to attack multiple times. After the first attack, being a circle, you should be beside him, but only for a moment, continuing his movement but still in control. Before the initial momentum of the attack has been spent, either while he's still committed to the strike, or as he's pulling back, recovering, this is the time to act, leading that movement into a technique. This is why many Aikido techniques look like the person receiving it is cooperating, they seem to be helping the person doing the technique, and in a sense they are. They give the opportunity and the strength, we merely guide them along the path until they are defeated, in effect by themselves. Circles are not stable in the stationary sense like the square, but they are stable in that they never fall. This is because they constantly move. Try to make a ball fall over... An example of the circular principle would be an attack from a sword. If the swordsman is committed to the strike, then the proper movement would be to lead him forward. If the attacker is holding back or recovering from the forward momentum of the attack, than a technique to his rear would be more effective.

Square: But what if the attack is neither forward or backward? The theory behind a neutral attacker is to get him to move, possibly through an atemi (strike). This will destabilize his position and a technique may be performed. When O Sensei drew a square, he often wrote the word go, meaning strength. He said that since a square was made up of four ninety degree angles, the most effective strike would be at a ninety degree angle. The square is a very stable, very strong position, but it is unlike the triangle and circle in that it lacks movement. We often start off in a "square" frame of mind, being very calm and neutral. From here, if an attack comes, we can be very ready, and turn into a triangle and counter by entering, or by becoming a circle, to harmonize with the attack and put him down that way.

These ideas of shape are simply to give the practitioner something easy to think about, a visual aid while practicing. Understand that the three shapes should not be restricting your thinking in any way, and don't worry if you can't identify which shape you should be. Also know that these shapes are constantly changing, never stick to any one. We can start a conflict in a square shape, moving into a triangle for an Atemi, and then into a circle to perform the technique.

Recently I've been thinking a lot of this imagery, and during class I try to envision these shapes in their different states. Even during the warm-up exercises I can see the different shapes, and thinking of these while performing a technique is very helpful. Like an artist who is first told to reduce everything to geometric shapes, so do we. The triangle is very easy to see, usually associated with the stance, a stable yet directioned force. I noticed recently that the point of the triangle is often at one's center, and this makes sense, as this is the origin of all movements. The circle is also easy to see, I find it's usually the movement of the body and arms. Using the circle takes away the partner's chance to resist, because it's impossible to resist a force that can go any way, change instantly, surround you and control you before you really know what's happening. I have a hard time envisioning the square, as it is the most stable of the shapes, and not usually associated with the actual movements. It is the stability needed while in Kamae (ready stance), both physically and mentally. One must be physically grounded in order to produce an effective technique, and without the concentration, no matter how physically correct you are, the technique cannot work.

[The text below has been submitted by Patrick Augé Shihan]

The Art of Aiki es la más completa fuente de información sobre el Aikido en Español. |

The Art of Aiki es la más completa fuente de información sobre el Aikido en Español. |