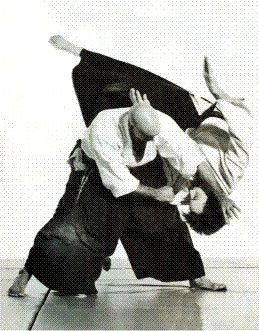

Since I practice both a traditional martial art (aikido) and mixed martial arts, I often get caught up with lots of arguments and discussions about the relative merits of the two. It's a touchy subject, since experienced TMA practitioners are highly invested in their arts, and MMA practitioners often have TMA experience that they "outgrew", so personal bias comes into play a lot.

For me, the two are not competing against each other, they are orthogonal in their attributes, overlap some, and only become antagonistic when someone postulates an either-or scenario. This is very similar to debates about religion vs. science or faith vs. evidence.

First, let's get some definitions out of the way. For me, a traditional martial art is one that emphasizes martial artistry along with cultural and character attributes. They are generally very formal, have a rigid hierarchy (often denoted by titles such as 'master', 'sifu', and 'sensei' and colored belts indicating rank), and tons of splinter groups and off-shoots from "mainlines". Examples of TMAs include the various flavors of aikido; karate-do; judo; tae kwon do; kung fu; wing chun; and Brazilian jiu-jitsu. Most of these arts also claim to be extremely effective in self-defense situations and/or particularly lethal, an assertion based on their heritage and not on evidence.

Related to these are what I call "sporting martial arts". These are combat sports that are generally one-dimensional, have competitions governed by rigid rules, and often lack formal or culturally steeped rules of etiquette. Amateur wrestling, boxing, and, to a lesser degree, Muay Thai kickboxing are examples of this. Ironically these don't really claim to be strong for self-defense due to their one-dimensional nature, but their training methods make them surprisingly effective for that purpose. BJJ is a sporting art as well, but its roots are in self-defense and NHB fights so I don't put it in this classification.

A mixed martial art combines the techniques of multiple combat sports and martial arts, and eschews the rigorous rules of conduct and hierarchies typically seen at a traditional martial art. MMA practitioners train at a gym (not a dojo or kwoon), don't have a belt system, don't practice forms or kata, and work under a coach.

MMA arose in two big steps.

The first was Bruce Lee's introduction of the Jeet Kune Do philosophy, which discarded the dogma of "you train under one style only" in favor of "use those techniques which work, discard the rest". This was a revolutionary concept at the time (if you ignore a couple of the "ancient MMAs" such as aikijujutsu and ancient Greek pankration) and counter to the rigid mindset of so many traditional martial arts.

The second step, and quite possibly the most important, was the arrival of mixed martial arts as a sport, with organizations such as the UFC, Pride, Rings, various K-1 derivatives, IFL, Cage Rage, Rumble on the Rock, and so on providing fight cards and venues. This greatly popularized the sport of MMA and, at the same time, the notion of MMA as a martial art in its own right.

And it was about this time that the TMA crowd freaked the fuck out. To understand why, you need to realize that traditional martial arts typically do not have full contact sparring with "anything goes" type rules. Almost all TMAs require a uniform that is very unlike street clothes. Each style limits the techniques for sparring to emphasize that style's strengths. Almost all striking styles (tae kwon do, kyokushin, goju ryu, et. al.) disallow clinching, throws, or joint locks during sparring; often require heavy padding; and in some cases disallow many types of practical strikes (TKD doesn't allow knees or kicks to the leg; kyokushin does not allow punches or elbows to the face). Almost all grappling styles (judo and Brazilian jiu-jitsu) disallow striking during sparring.

There's nothing particularly wrong with all that, but these limitations mean that a style's effectiveness is a matter of faith. Too often bold claims were made about a particular style's lethality, i.e. "I could use these killer techniques but I'd maim you, so I can't spar". This is, not to put too fine a point on it, bullshit.

Why is it bullshit? Because, as Jigoro Kano (creator of judo) discovered almost 100 years ago, if you do not practice your techniques against a fully resisting opponent, then you have not mastered that technique. That is an absolutely unavoidable reality. If you possess some devastating joint break or nose smash or eye gouge or throat crush that you've never actually used it, then there's no way you can tell if it's effectiven (in absolute terms) and if you've really mastered it.

This is where many sporting martial arts (and judo, which is part TMA and part sport), developed a practical advantage, even with huge gaps in their curricula. A practitioner of a sport art competes against others on a regular basis, exposing them to opponents that do not want a technique performed on them. By using only techniques that won't kill someone, combatants can use their full repertoire at full speed and power.

This has a couple benefits. The first is that a student truly learns how to use a technique, under duress, and under less than ideal circumstances. This cannot be emphasized enough. The second is almost entirely intangible -- the student learns to deal with conflict and confrontation at high speed. Many TMAs train students using rote partner drills or unrealistic attack patterns (aikido's randori). The student's mettle is rarely tested against an attacker using skills or strategies outside that TMA's comfort zone.

A boxer may not be great at take downs or kicks, but he's usually very comfortable having someone trying to knock his head off. A wrestler may not have good striking skills, but he's used to someone trying to tackle him and slam him to the ground. Real world experience will trump theoretically dominant skill sets almost every time.

Now, MMA is the polar opposite of a TMA when it comes to the effectiveness of a technique -- it is purely evidence based. Faith doesn't play into it. Techniques are researched, developed, enhanced, and then tested in the crucible of a mat, ring, or cage. Techniques that simply do not work very well eventually fall by the wayside, so you have an accelerated evolutionary mechanism at work.

Over the past 15 years this has been strikingly evident in the MMA world. In the early days of the UFC you had Brazilian jiu-jitsu guys dominate using very rudimentary take downs and almost no striking skills. Over time wrestlers with superior take downs and take down defense, but sub par striking and submission abilities, started to dominate the scene. Then fighters like Fedor, BJ Penn, Wanderlei Silva, and GSP started showing up. They would use Brazilian jiu-jitsu submissions, wrestling take downs and take down defense, boxing punches, and Muay Thai kicks and knees.

MMA practitioners today are much, much different than those of even 10 years ago. An MMA fighter today probably still specializes in one domain, but he will be at least "good enough" in every other facet of the game or he won't be competitive. This is the evolution of MMA today.

MMA techniques and training regimens are based on evidence, not faith. You don't learn a technique with a master scowling at you saying "This will work when you need it, trust me!" If you can't pull off something, you won't use it, and you'll find out soon enough if you can pull it off.

TMAs, on the other hand, don't have the laboratory of no-holds barred competition with which to evolve, which is why, by and large, the goju-ryu or wing chun of today is nearly identical to that of 50 years ago.

TMA practitioners have their counterarguments when it comes to pure combat efficiency. The most common is that a TMA isn't a "sport" and thus is potentially more lethal. But as I discussed earlier, if you have a host of lethal techniques that you've never used against someone trying to beat the crap out of you, it's doubtful that you'll be able to use them when the shit hits the fan. The second most common, and ironic, argument is that a TMA is more effective "for real" since MMA competitions occur inside a regulated ring, wearing protective gear, minimal clothing, no weapons, and a well-defined one-on-one scenario.

This claim of "more realistic" would have a lot more weight if TMAs regularly trained in street clothes, wearing shoes, with weapons, against multiple opponents, and outside on concrete or inside on hardwood floors -- using a wide range of techniques. But they don't, making the argument specious at best.

So all that said, I must be pretty down on TMAs, right? NOT AT ALL! As I said at the beginning, I still practice a TMA (aikido) regularly. And here's why: MMA and TMA offer completely different things.

If you want to learn how to fight, then I do strongly believe than an MMA is going to be far more effective than any TMA in existence. It's faith vs. science -- I have evidence of MMA effectiveness and, more importantly, as I progress with MMA I can test my own abilities. It is true that MMAs are really optimized for fighting against someone who also has training, but I don't consider that a liability. Many TMAs are really setup to fight against others of their own style or against completely untrained opponents.

But not everything is about fighting. TMAs offer a host of valid benefits:

- minimal but real exposure to history and cultural information

- a feeling of learning an art form. For many people things like kata, practice drills, etc. are relaxing all on their own.

- flexibility, strength, and cardiovascular improvement

- relaxed environments where you can hang out and have a good time without feeling competitive pressure

- a feeling of accomplishment based on your own advancement, not on your competitive ability

For some these benefits are absolutely massive. There are people that would be woefully uncomfortable wearing board shorts, rashguard, and mouthpiece while getting the shit kicked out of them. For your average house wife or mid-40s executive, something like tai-chi or wing chun or shotokan may be just what they're looking for.

An MMA practitioner poo-pooing those elements is missing the point entirely -- those features of a TMA aren't meant to appeal to an MMA practitioner hell bent on crushing the opposition.

If you want to learn how to

fight, then MMA is the answer. But MMA training would leave a lot of people empty and cold, people who would otherwise find deep satisfaction with a TMA.

The analogy is religion vs. science. Religion doesn't make a lot of sense to a lot of people, and it may not be practical as a cure for cancer or your financial problems, but it's a source of wonderment, comfort, and camaraderie with like minded individuals. And this is what TMAs are like.

Science won't comfort you or tell you what you want to hear, but it will provide data in a measureble, repeatable format based on experiments and observed behaviour. It is up to you to draw what you can from MMA, but it cares not for your own needs. But you can rely on it to be fairly objective or, more callously, uncaring.

And as in the modern world, religion and science are not mutually exclusive, unless you choose to put them at odds with each other. TMAs and MMAs can coexist as long as you understand their roles and accept their limitations. And if you choose not to do both, that's great, but don't disparage the other because you're projecting your values onto something that isn't a good fit for you.

[Fuente: mma-journey.blogspot.com]

The Art of Aiki es la más completa fuente de información sobre el Aikido en Español. |

The Art of Aiki es la más completa fuente de información sobre el Aikido en Español. |